By David Pariser, Professor of Art Education, Concordia University, Montreal, Quebec.

Camden, Maine — The Community School’s National Advisory Board held a conference on May 8 to mark the school’s first 25 years and honor the remarkable students, staff, administrators, sponsors and community who have helped this alternative school to grow and thrive.

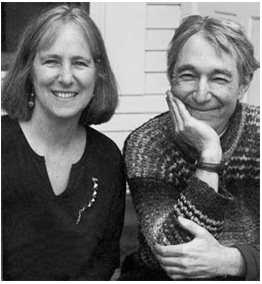

The Community School is the brainchild of co-founders Dora Lievow and Emanuel Pariser, who started this venture in 1972 with a truly Quixotic optimism. Their vision: Creating a school for adolescents where staff and students built the core activity of teaching and learning on the concept of Relational Education — establishing a foundation of mutual respect and trust between teacher and student.

Cschool hosted the May 8 meeting to do more than to simply say a much-merited “Congratulations!” to everyone involved in the institution’s vigorous longevity. Participants spent the morning working together in small-group sessions. In the evening, a ten-person panel composed of educators and a Cschool graduate presented an evening of commentary and discussion to an audience of 80 people at the Camden Opera House.

In her opening remarks, Maine State Representative Judy Powers said had moved to mid-coast Maine at the same time as Dora and Emanuel had founded the Cschool. She said that the consistently high level of commitment, respect and responsibility that she had observed over the years in all her contacts with the Cschool staff had impressed her.

State Rep. Powers quoted Cschool’s most recent Annual Report to describe the school’s moral compass: The school aims to instill in all its students “an ethic of respect and an expectation of personal responsibility.”

“What would our society be like if all our high schools described themselves as doing these things?” State Rep. Powers asked.

Fred Bay, executive director of the Josephine Bay Paul and C. Michael Paul Foundation, served as panel moderator — but he first exercised his speaking privilege. He pleaded with the audience to spread the word, as he does, that the Cschool is every bit as “real” an institution as any 3,000-seat urban high school. Whenever he has the opportunity, Bay said, he refers to the Cschool as one of the most successful high schools in the country.

Under Bay’s genial and well-spoken supervision, panelists began their discussion by debating possible connections between alternative education as practiced at the CSchool and prevention programs for adolescents. The group first attempted to identify Relational Education’s special features, and the ways that it serves two educational goals.

Relational Education’s approach emphasizes the cultivation of a broad-based level of interaction between tutor and student. The tutor becomes a great deal more than simply a conveyor of information, while “learning” comes to entail a great deal more than the acquisition of facts.

If emotional, personal and life issues obstruct students from the learning task at hand, Relational Education teaching sessions become times when students can express themselves. This “personal material” is seen as part of the lesson’s content. Though including this sort of personal material is a delicate matter, doing so tends to make the learning sessions much more effective by generating a higher level of trust between students and teachers. In “regular” classrooms, where there is neither time nor place for personal issues, the level of trust is lower.

Cschool’s approach does double-duty: It facilitates the process of learning while it provides students with the necessary emotional and intellectual tools to begin to cope with the ugly realities that they have and will continue to face, such as substance abuse and violence.

A number of participants agreed that separating “prevention” from “teaching” creates a false distinction. Professor William Davis, director of the University of Maine’s Institute for the Study of Students at Risk, said that some of the people in charge of conventional schools believe in the false idea that there is a neat divide between so-called “cognitive” issues and “mental health” or life issues.

“Many of the things that we are talking about constitute real barriers to learning. It’s not either/or,” Davis said. “It’s not something you can get at some other time. For many youngsters, the reason that they are not learning is because other parts of their being are not being attended to.”

The discussion turned to systemic problems in educational institutions, their causes, effects, and the alternative remedies that the CSchool could offer. That the Conference took place within a few weeks of the Columbine High School shootings did not pass unnoticed. Educational consultant Arnie Langberg, who lives in Colorado, said that this tragedy underscored the fact that those who plan and run schools are simply out of touch with the way that students experience these institutions.

Paths of Learning magazine’s Executive Editor Ron Miller spoke about the history of Western schooling and the ways in which this institution has drifted further and further from the most basic and natural settings for instruction. He pointed out that education in non-schooled societies is a community affair, while modern education is an artificial solution to a social need.

During the last two centuries, Miller said, schools in the industrialized world mostly served the purpose of fitting people into social slots in an expanding industrial economy. Yet it is becoming evident to anyone with the capacity to observe and to draw conclusions that American schools — especially our high schools — have failed to address some basic needs among their students.

Those who plan and run schools have lost sight of the fact that healthy learning requires communal support both within and outside of the school. The more complex, anonymous and sterile that high schools become, Miller said, the more likely it is that some students will respond with destructive rage.

Though the panelists were critical of the schools, they never cast blame on teachers or administrators. Davis emphasized that, “There are many, many teachers in public schools who care desperately about doing the very things that people are talking about here today. There are many administrators who care, care desperately in terms of trying to help kids.”

MacArthur award-winning Principal Deborah Meier of Mission Hill Public School in Roxbury, MA said that the autonomy of adults and children became increasingly compromised as schools grew in size for reasons of economic efficiency.

“We created schools in which not only young people were powerless, but adults were powerless,” Meier said. “More and more, not only were young people not known by these adults, but these adults were not adults who could help them learn to be grownups.

“You can’t learn to play basketball without having basketball players. We have asked our young people to grow up into grownups in the absence of people who are powerful models of what it could be like to be a grownup,” Meier said. “In fact, the most common experience in school aside from the teaching experience is that grownups will say to them, ‘Well, that’s just the way it has to be….’ They experience powerless grownups, and if there is anything young people don’t want to be surrounded by, it is powerless adults.

“We need to create schools the way the Cschool has, in which young people not only gain more power for themselves but experience what it is like to be with powerful adults,” Meier said.

Community School graduate Brenda Wentworth, a substance-abuse counselor with the Health Reach Network, concluded the panel discussion with vivid reflections on how the CSchool gave her some of the emotional and intellectual tools that she has used since. She painted a moving and dramatic picture of the way in which her own one-on-one tutor at the school had shown her the sort of respectful affection that had eventually opened her mind and heart to making changes in her life.

Reflecting upon her growth and her remarkable achievements as a Master’s student, Wentworth was able to identify the tell-tale points where traditional teacher-student interactions come to grief. It’s about power, she explained, and when teaching degenerates into a contest of wills the, situation is hopeless. Somehow, Wentworth’s tutor was able to avoid this dead end, and now she is able to approach others in need, with the special emotional and cognitive skills that she learned during her hard but hopeful stay at the Cschool.

As Meier put it: “Respectful affection is the key to learning math as well as learning how to be a grownup.” Respectful affection is the basis for relational education as implemented at the CSchool.

Dora Lievow and Emauel Pariser, Co-Founders of The Community School